A GREAT TIME FOR FANTASY

TUES, FEB 10, 2026 - 10:37

It's undeniably a great time for fantasy.

Nowadays, with tech capabilities and audience demand converging pleasantly like sugar and butter, we're getting a slew of new material to enjoy. And the latest news in this area came just two weeks ago when Brandon Sanderson and Apple signed an unprecedented" deal (in Hollywood Reporter language), giving Apple the rights to Sanderson's expansive, beloved, and undeniably delicious fictional universe, the 'cosmere'.

The deal is rare one, coming after a competitive situation which saw Sanderson meet with most of the studio heads in town. It gives the author rarefied control over the screen translations, according to sources. Sanderson will be the architect of the universe; will write, produce and consult; and will have approvals.

- The Hollywood Reporter

I couldn't be happier about this.

First of all, I'm a Sanderson fan. Secondly, I'm an Apple fan, and I've been delighted with almost everything AppleTV has cooked up so far. Like Apple itself, it seems that AppleTV shares their parent company's desire for high-quality and attention-driven design, and it's equally evident that a respect for the source material is also part of their ethos – all of which forges excellent TV. The hit-rate for good shows on AppleTV is undeniably good, as a quick glance at IMDB or Rotten Tomatoes will confirm. Severance, For All Mankind, Ted Lasso, See, Silo, and Foundation have all been excellent.

Foundation in particular has demonstrated that mature, complex and high-quality fiction is not only viable but that audiences are hungry for it. Again, as a huge fan of Isaac Asimov's work, I consider it an excellent re-imagining of the source material. It's different but in all the right ways, stays true to the heart of the works, and adds some new layers which the books lacked but which elevate the series (adding the 'genetic dynasty' was a masterstroke, allowing continuity, familiarity, and a lens through which to view the crumbling of Empire effectively, for example).

All-up, AppleTV productions are some of the best out there and, perhaps most impressively of all, Apple has somehow avoided letting current social or political trends or slants sully the production (unlike some other studios, namely 'Amazon', 'Netflix', & 'Disney'…).

So, you can see why I'm excited. If everything pans out, we're going to get some stellar new fantasy material to sink our teeth into, though it's going to be a few more months before anything more concrete is announced. All I'll say for now is that seeing as Sanderson himself is slated to retain a lot of creative control, I think there's reason for hope on this one.

Hear Brandon speak about this exciting deal himself on his YouTube.

Here's to that, fellow fantasy freaks!

Jim :)

NEW: JAMES McLEOD'S ‘THIS EMERALD CRUCIBLE' HITS THE SHELVES

THU, JAN 15, 2026 - 09:00

Ladies and gentlemen, gikkans and paddoneks; after many teasers and trailers and tantalising hints, a new chapter in the world of Aliru has officially arrived!

‘This Emerald Crucible’, the newest fantasy-adventure from James McLeod, is available from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and online retailers everywhere - and it’s set to rock the boat in more ways than one…

PAPERBACK & EBOOK AVAILABLE NOW!

BUY ON AMAZON

OFFICIAL WEBSITE

VIEW TRAILER

Neither sequel nor prequel, more of a skewquel, this story takes place in the same world as The Torril City Mysterion, but in a different time and place, featuring a new host of characters. If you’ve read Torril City you’ll find tantalising tidbits strewn through the tale but, if not, this story can be experienced on its own as an introduction to this vast and mysterious world.

Reiuk hates people and loves plants, but when he’s sent to the strange, tropical island of Taen Lua, he’ll have to overcome his inner-furor if he’s going to survive the jungle, the people, and the ancient mysteries he’s suddenly confronted with…

Reiuk hates people and loves plants, but when he’s sent to the strange, tropical island of Taen Lua, he’ll have to overcome his inner-furor if he’s going to survive the jungle, the people, and the ancient mysteries he’s suddenly confronted with…

Today is a special day, and one which I’ve looked forward to for a few years now. It’s a day on which I can now share the world I’ve been living in since 2018. If you pick up a copy, I really hope you enjoy it. As always, the aim is to delight and thrill my readers with excellent fantasy and adventure, and I hope this story lives up to that goal.

PRAISE FOR THIS EMERALD CRUCIBLE:

“IT’S ALWAYS A PLEASURE TO READ […] and see another aspect of Aliru. "This Emerald Crucible" is an epic, secondary world fantasy […] disguised as a cosy murder mystery.”

- L.A. Reader

"THE PROTAGONISTS ARE DELIGHTFULLY DYSFUNCTIONAL, but here is a story of transformation and hope."

- Moritz Kobler

"A ROLLICKING GOOD RIDE. This tale sings with drama, mystery and magick. I'll never forget it!”

- Harakar, Chronicler & Adventurer

"McLEOD'S LOVE OF HISTORY is evident throughout the beautiful world he has crafted."

- Tu'Sum, Royal Historian

THIS EMERALD CRUCIBLE is a PART ONE of OF SAND AND SOIL, a story set in the world of Aliru.

Cheers!

Jim :)

THE MARINER SETS SAIL!

THU, DEC 11, 2025 - 14:27

Fantasy fiends, ahoy! The giving season has officially begun, so what better time to drop a little gift on you all?

If you’re in the mood for a tale of adventure, magick and mystery on the high-seas, head over to the Short Story Library and cast off with The Mariner!

VISIT THE LIBRARY

I’m so happy it’s finally ready to share with you all and, as usual, it’s free!

An audiobook version is on the way, so stay tuned for that.

Until then, peace!

Jim :)

INDIE AUTHOR BOOK FAIR 2026

FRI, NOV 14, 2025 - 10:01

Come and meet James McLeod at

The Indie Book Author Fair

SUNDAY, JAN 11, 2026. 9am to 4pm

Barwon Heads Community Hall, 77 Hitchcock Ave, Barwon Heads VIC 3227, Australia

Visit the official website

Yes, the Indie Author Book Fair is taking place once again in Barwon Heads, Victoria, and I’ll be there with a stack of books, a fashionably medieval table-covering, and a few free smiles (for those who really want one).

It's a beautiful location, close to the surf and sand and doused in fresh sea-air. So if you’re in the area, why not come along and say hi? I love meeting readers and chatting about fantasy, writing, and all things magickal. Plus, there will be heaps of other indie authors there too, so it’s a great opportunity to discover new voices and stories.

The event runs from 9am to 4pm at the Barwon Heads Community Centre and rumour has it that I'll have a freshly-released fantasy novel on offer!

Hope to see you there!

Jim :)

STORYTELLERS

SUN, SEP 07, 2025 - 14:26

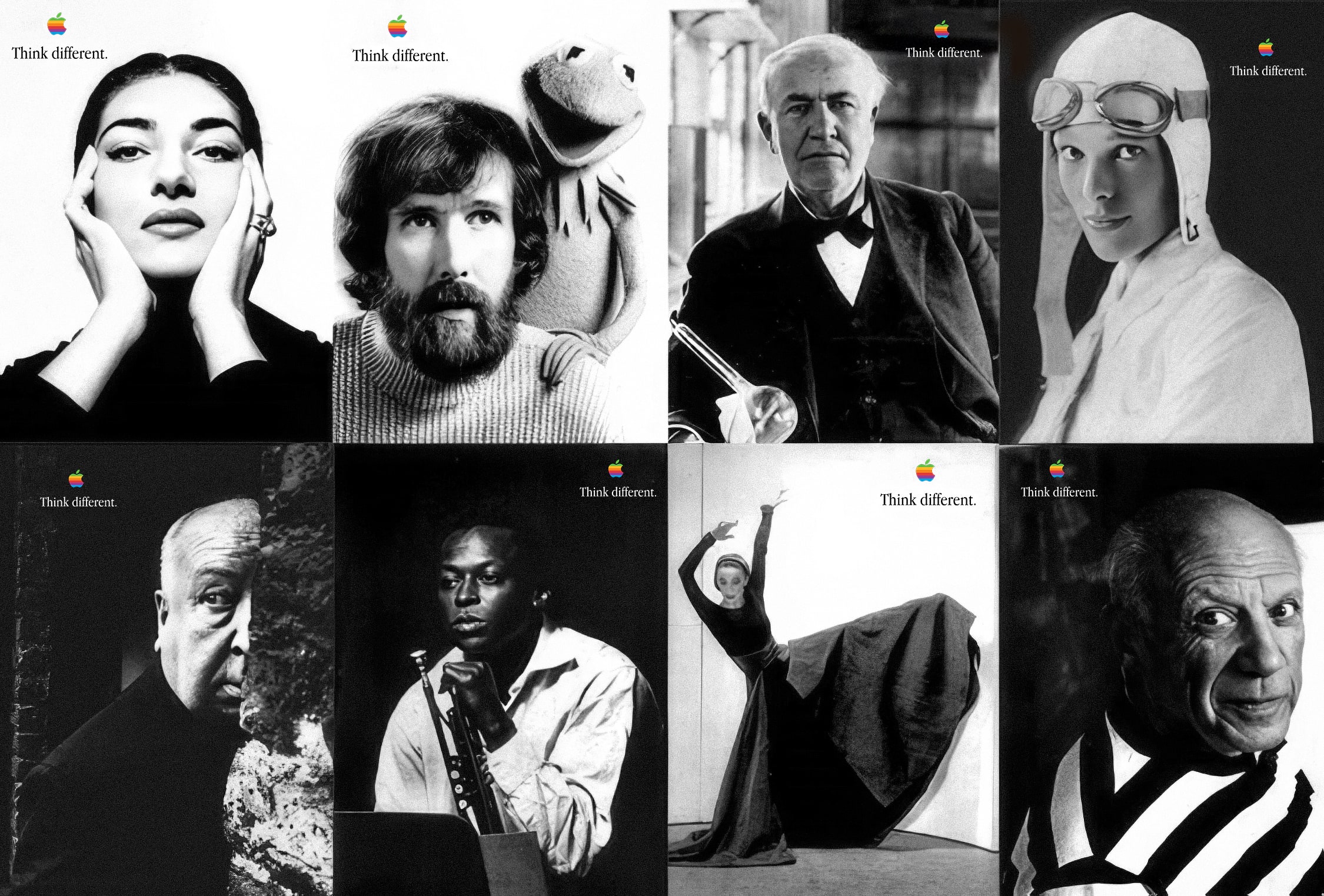

Here's to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels. The troublemakers. The round pegs in the square holes. The ones who see things differently.

They're not fond of rules. And they have no respect for the status quo. You can quote them, disagree with them, glorify or vilify them. About the only thing you can't do is ignore them. Because they change things. They push the human race forward.

And while some may see them as the crazy ones, we see genius. Because the people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world, are the ones who do.

In the late 1990s, Apple ran an advertising campaign which not only summed up the company’s ambitions at the time, but defined heart and soul of their efforts for the next 20 years.

The ‘Think Different’ campaign was not just haughty-sounding advertising jargon. The slogan and accompanying manifesto told a story about Apple; where they were, who they wanted to be, and what kind of customer they were speaking to. It celebrated the outlier and spoke to a generation of artists, filmmakers, songwriters and dreamers who grew up in the confusion and drama of the 1980s.

To really hammer this point home, the TV and print ads featured a montage of famous ‘crazy ones’ — including Albert Einstein, Bob Dylan, Martin Luther King Jr., John Lennon, Mahatma Gandhi, Amelia Earhart, Pablo Picasso, Thomas Edison, and many more. It was a roll-call of creative and courageous visionaries and rebels.

Apple's 'Think Different' campaign rounded-up some famous faces like Pablo Picasso, Amelia Earhart, and Jim Henson.

Apple's 'Think Different' campaign rounded-up some famous faces like Pablo Picasso, Amelia Earhart, and Jim Henson.

It's no surprise that Steve Jobs loved the campaign. His goal for Apple had always been to 'sell dreams' and to do that, he knew that Apple needed great storytelling.

Clearly, Apple found it, and 'selling the dream' is a talent which Apple has cultivated carefully over the years and never let slip. From the 1980s right up to today, from the original Macintosh launch in 1984 to Vision Pro in 2023, Apple has consistently used storytelling to create emotional connections with its audience, with product launches not just about specs and features; but tales which resonate with people's aspirations and values.

This is not a novel concept, of course. Car, cologne and beer companies all clued into the fact long ago that to sell a product well, that product needs to represent a lifestyle. What sets Apple apart is that their storytelling is not limited to marketing material, but has been quietly woven into their product line and ecosystem.

This year, Apple is going to release MacOS 26 (Tahoe), which introduces a new design language called 'Liquid Glass'. This is not just a gimmick or visual overhaul; it’s narrative development. It's Apple's way of signalling its ongoing commitment to innovation, user experience, and design excellence. And perhaps more importantly than that, it's about showing users the future of computing — or at least the future that Apple wants.

Liquid Glass is a triumph of UI design. A mix of solid and fluid, an ode to playful elegance, and a replication of real-world physics in the digital space — and that last point is important.

With the introduction of Vision Pro, Apple aimed to changed the way we think about computing. This device embraced a new way of interacting with digital content, blending the physical and virtual worlds, and signalling depth with shadow, transparency, translucency, and movement. Apple clearly wants to carry this new paradigm into its other products. Liquid Glass is therefore not just a big step forward in user interface design, it’s a way for Apple to tell their story about the future of computing and get people ready for what's coming next.

The new Liquid Glass UI language is elegant, playful, and future-facing.

The new Liquid Glass UI language is elegant, playful, and future-facing.

Of course, Apple has its critics. Since the announcement of Liquid Glass, howls of indignation have erupted across the internet, with some pointing out that the update is an 'accessibility nightmare!' with low readability or poor contrast (complaints which must willfully be ignoring the fact that Apple has for a very long time had perhaps the best Accessibility options in the entire tech sphere, with settings galore for altering the OS to be more readable or higher-contrast or so forth). Or that it's gimmicky and 'too like Windows 11', which is not a little insulting to Apple's design team…

It's often said that since Steve Jobs passed away in 2011, Apple has lost its way. That it has 'stopped innovating' or can't produce revolutionary products anymore. This, in my opinion, is absolute nonsense. Apple under Tim Cook has been fantastic.

Consider the Apple Watch, Airpods, Vision Pro, the M-series chips, the seamless ecosystem features like Handoff, Face ID, Continuity Camera, Live Translation, AI‑powered tools (alright, that's still being ironed out), all of which have appeared under Cook's tenure. Cook has overseen the biggest period of growth in Apple's history, and the company is now the first to reach a $3 trillion market cap. Not bad for a company that's supposedly 'losing its way'.

To me, MacOS Tahoe is another example of Apple’s ongoing commitment to innovation and product excellence. Despite all the criticism and bluster out there, actually using the updated OS is a joy. On iPad and iPhone, elements move and flow and respond to your touch in a way that feels natural and intuitive and fun, while on the Mac, things are toned down a little but still look absolutely 'lickable', as Steve Jobs once put it. The OS feels cleaner, snappier, and feels ready for the future in a way that, as usual, is going to be mighty hairy for the competition to try and copy (though they will undoubtedly try).

In fact, a strange thought occurred to me when it was announced; that in a way we've come full-circle. 25 years ago in 2000, Apple introuced 'Mac OS X', its tenth Operating System and complete re-write using a flashy new Unix core. The OS featured an interface called 'Aqua' which — as the name implies — was inspired by water.

The 'Aqua' interface of Mac OS X bears more than a passing resemblance to Liquid Glass, with jelly-buttons and translucent panes.

The 'Aqua' interface of Mac OS X bears more than a passing resemblance to Liquid Glass, with jelly-buttons and translucent panes.

It looked amazing at the time. Corners were rounded, icons were translucent and glossy, and the whole thing felt fresh and new. It was a big leap forward from the old 'Mac OS 9', which by comparison felt clunky and primitive. And yet, Aqua was limited by the technology of the time. Screens were smaller, processors were weaker, and the best Apple could pull off in terms of fluidity was the 'genie' effect when minimising windows.

Now, 25 years later with Liquid Glass, it seems that Apple is finally able to realise that original vision in a way that feels modern and relevant. Indeed, my first thought upon seeing Liquid Glass was, 'this is the Aqua Steve wanted.'

The homage is poetic. Both the end of a story, and a whole new beginning for Apple.